welcome to Impact Factoryour weekly dose of commentary on a new study in medicine. I am Dr. F. Perry Wilson, from the Yale School of Medicine, in New Haven, United States.

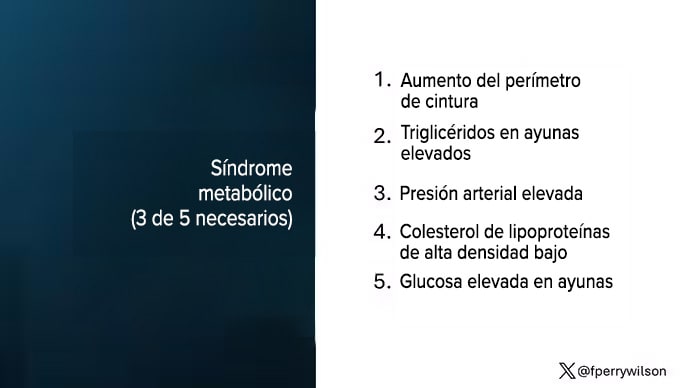

One in three American adults—about 100 million people in that country—lives with metabolic syndrome. Below I show you the official criteria, but essentially it is a syndrome of insulin resistance and visceral adiposity that predisposes us to a series of chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart disease and even dementia.

Metabolic syndrome is, fundamentally, a disease related to lifestyle. There is a direct relationship between the increase in the syndrome in the population and our eating habits and the wide availability of carbohydrate-rich and highly processed foods.

A saying I learned from one of my epidemiology professors comes to mind: “Lifestyle diseases require lifestyle reinterventions.” But you know what? I’m not so sure anymore.

I’ve been around long enough to see multiple diet fads come and go with varying effectiveness. I grew up in the era of low-fat diets, probably the most detrimental to our country’s health, as food manufacturers began substituting carbohydrates for fat, which caused much of the problem we face today. .

But I was also around the time of the Atkins diet and the low-carb fad: a healthier approach, all things being equal, and I’ve seen variants of them: the paleo diet (essentially a low-carb, high-carbohydrate diet). proteins based on minimally processed foods) and the Mediterranean diet, which sought to replace a certain percentage of fats with healthier ones.

And, of course, there is the time restriction.

Scheduled feeding, a variant of intermittent fasting, has the advantage of being very simple, without cookbooks or recipes. Eat whatever you want, but limit it to certain times of the day, ideally to a period of less than 10 hours, like 8 a.m. to 6 p.m.

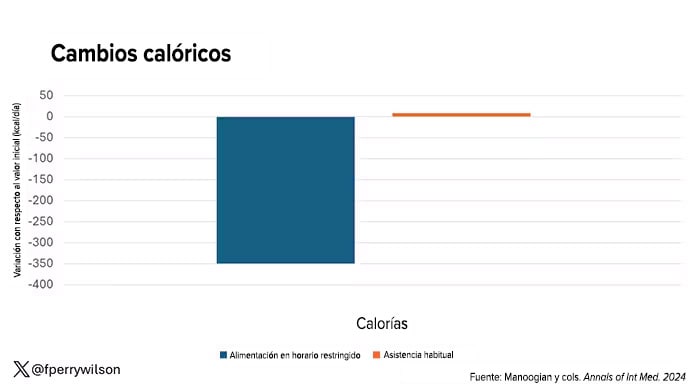

When it comes to losing weight, diets that work usually do so because they reduce calorie intake. I know, people will anger For this reason, but thermodynamics is not just a good idea, it is a law.

However, weight loss is not the only reason we should eat healthier. What we eat can impact our health in multiple ways; certain foods result in more atherosclerosis, more inflammation, more stress on the kidney and liver, and can affect our glucose homeostasis.

So I was very interested when I saw an article published in Annals of Internal Medicine at the beginning of October, in which the effect of restricted feeding on metabolic syndrome itself is examined. Could this lifestyle intervention cure this disease?[1]

In the study, 108 people, all with metabolic syndrome but not diabetes, were randomized to usual care—basically, nutrition education—versus restricted-schedule feeding. In that group, participants were instructed to reduce their eating schedule by at least four hours in order to achieve a food consumption period of 8 to 10 hours. They followed the groups for three months.

Now, before we get to the results, it is important to remember that the success of a lifestyle intervention trial depends quite a bit on whether people adhere to the lifestyle intervention. Time restriction is not as easy as taking a pill once a day.

The group leading the research asked participants to record their consumption using a smartphone application to confirm whether they respected the restriction.

Generally speaking, they did. At the beginning of the study, both groups ate about 14 hours a day (from 7 in the morning to 9 at night). The intervention group reduced this to just under 10 hours, with 10% of the days outside the target period.

Once lifestyle change was achieved, the primary endpoint was the change in glycated hemoglobin at three months. Glycated hemoglobin integrates serum glucose over time and is therefore a good indicator of the success of the intervention in terms of insulin resistance. But the result was, to be frank, disappointing.

Technically, the group that restricted the eating schedule did experience a greater change in glycated hemoglobin than the control group… by 0.1 percentage points. On average, they went from a baseline glycated hemoglobin of 5.87 to 5.75 after three months.

Other markers of metabolic syndrome were similarly lackluster: There were no differences in fasting glucose, mean glucose, or fasting insulin.

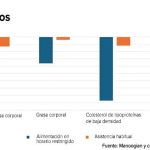

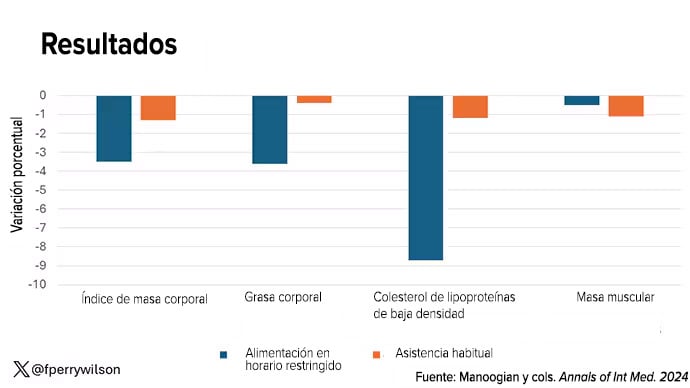

There were some weight changes. The control group, which received this dietary education, lost 1.5% of their body weight over the three months. The group with restricted feeding lost 3.3%, about 2.5 kilos, which is acceptable.

With this weight loss came statistically significant, although modest, improvements in body mass index, body fat percentage, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

It should be noted that, despite the greater weight loss in the intermittent fasting group, there were no differences in muscle mass, which is encouraging.

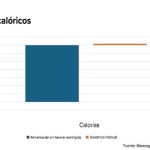

In short, we can say that yes, it seems that time restriction can help you lose weight. This is essentially due to the fact that fewer calories are ingested when feeding time is restricted, as can be seen here.

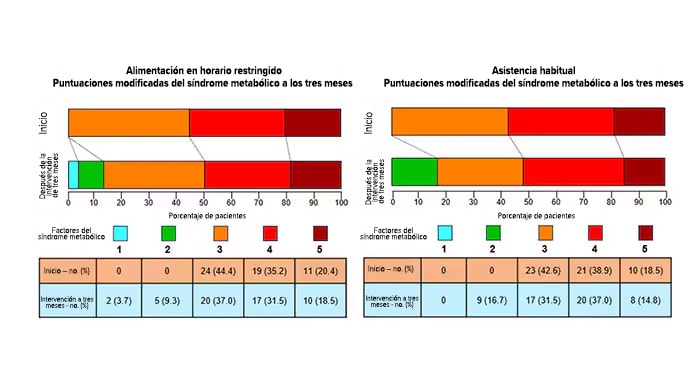

But ultimately this trial looked at whether that relatively simple lifestyle intervention would make a significant change in terms of metabolic syndrome, and the data are not very convincing on that.

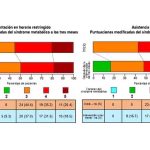

This graph shows how many of those five metabolic syndrome factors people in the trial had from beginning to end. You can see that, over the course of three months, 7 people in the time-restricted feeding group went from having three criteria to two or one, that is, they were “cured” of metabolic syndrome, so to speak. Nine people in the group with regular care were cured according to that definition. It must be remembered that they had to meet at least 3 to have the syndrome and, therefore, be eligible for the trial.

So I’m wondering if there’s something metabolically magical about time restriction. If it only leads to weight loss, because it forces people to consume fewer calories, then we have to recognize that perhaps there are better methods to achieve that same end. Ten years ago I would have said that lifestyle change is the only way to end the metabolic syndrome epidemic. Today… well, we live in a world with glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonists for weight loss. It’s just another time. Yes, they are expensive. Yes, they have side effects. But we have to evaluate them against their counterparts, and so far, lifestyle changes alone don’t hold a candle.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson, MSCE, (@fperrywilson) is an associate professor of medicine and director of the Yale Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. Her science communication work can be found on the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. His new book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now.

This content was originally published in the English edition of Medscape.