For most people, the idea of a conditioned reflex does not usually go much further than the evocation of Pavlov’s dog salivating at the sound of the bell announcing the imminent arrival of food. But, far from what may seem like a simple laboratory anecdote, Ivan Pavlov immediately understood, as great scientists usually do when faced with their discoveries, the relevance of these reflections in people’s lives. This was to the point that the significance that the Russian scientist attributed to his discovery made him surprisingly change his planned speech on digestion (a topic for which he was later awarded the Nobel Prize) at the International Congress of Medicine in Madrid in 1903 to give account of his recent discovery. In the end, he explained, for the first time before a scientific audience, conditioned reflexes or psychic secretions, as he called them then.

Humans react emotionally, with positive or negative feelings, to names or images of people, places or things that we are not necessarily familiar with, without often knowing or understanding why. Whoever feels animosity or affection towards a certain person, such as a politician or an athlete, or towards a means of communication, a melody, a work of art or a specific city or place, will not always be able to explain why, that is, You will not always be able to provide logical and convincing reasons for those emotions raised. But, Pavlov’s dog salivating, these emotions are transcendent because they are stimuli or conditioned reflexes that hijack our behavior, preventing us from acting against them.

Neuroscience has discovered the mechanisms that make conditioned reflexes possible, also called classical or Pavlovian conditioning, which has been especially studied by the American researcher Joseph LeDoux in the laboratory rat. In their basic experiment, an acoustic tone is played immediately before the animal receives a small electric shock in its paws through the bars that form the floor of its cage. If this tone-shock sequence is repeated several times, the rat ends up associating the tone with the shock and as soon as it hears it it remains motionless, frozen, that is, it learns that the tone indicates the imminent arrival of the electric shock to its legs and then you feel fear, a form of emotional memory. The tone, which is initially a neutral stimulus, thus becomes a conditioned stimulus, capable of inducing fear in the rat even when it is not followed by the electric shock.

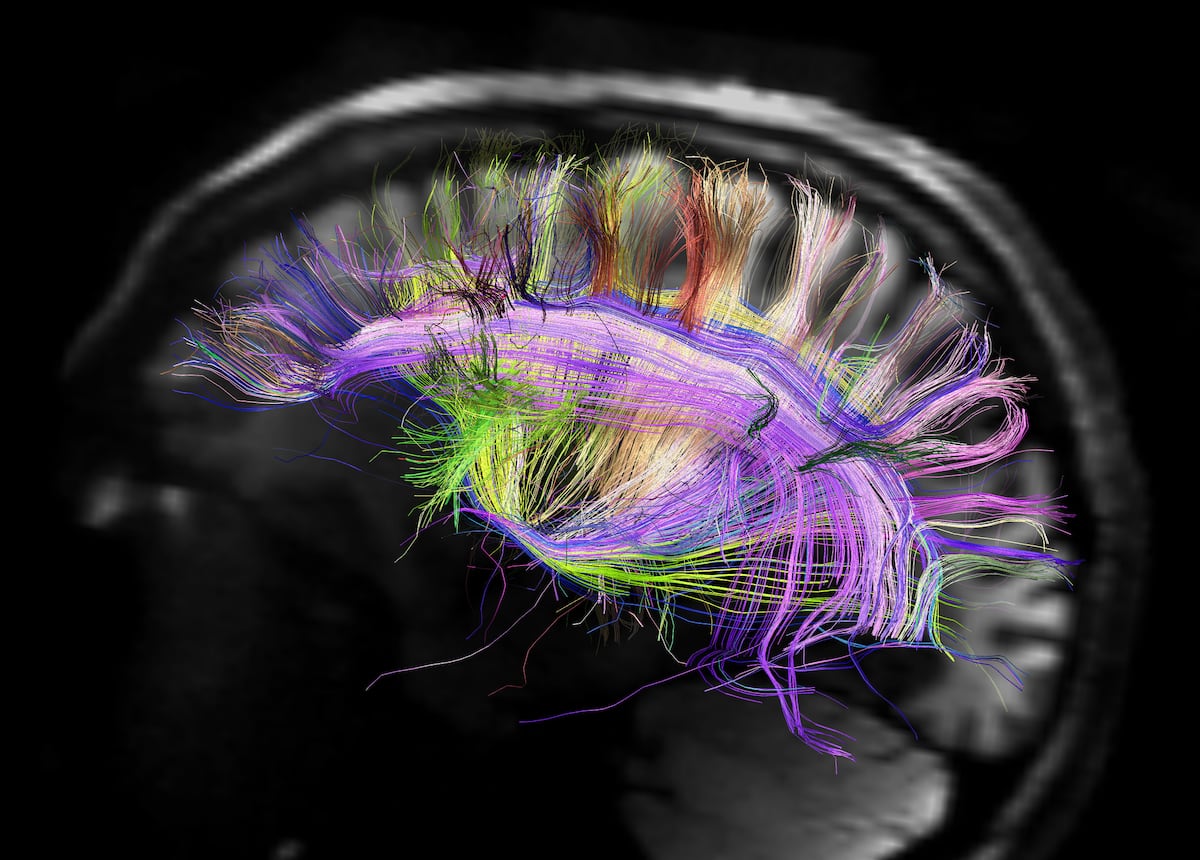

The changes caused by this fear learning take place in the amygdala, a structure in the temporal lobe of the mammalian brain. It contains the neurons where the information about the tone converges with the information about the electric shock. When this convergence occurs repeatedly, the synapses or connections of these neurons are enhanced and therefore increase their capacity to activate new neurons also in the amygdala, which are the ones that, acting on other parts of the brain, generate the fear response, that is, the immobility of the animal, the increase in its heart rate and the release into the blood from its adrenal glands of hormones such as adrenaline and corticosterone. This set of behavioral and physiological responses also act simultaneously on the animal’s cerebral cortex, generating or enhancing a concomitant feeling of fear supposedly similar to what humans experience in equivalent situations.

This mechanism, universal in mammals, explains that people can have emotional responses of fear when a dangerous situation, real or imagined, such as the accident of the vehicle in which we travel, the loss of a job or a romantic breakup is associated with the cerebral amygdala to the people or the place where those events occurred. In this way, an emotional memory is formed that will cause those stimuli, such as associated people or places, to arouse fear or animosity in the future when we imagine them again or appear in our presence, without necessarily being experiencing the original negative situation. This conditioned emotion, which can also occur in relation to positive events or circumstances, is what hijacks our behavior, making us reject or distance ourselves from the people or places involved in the original negative conditioning. Pavlov saw it before anyone else.

gray matter It is a space that tries to explain, in an accessible way, how the brain creates the mind and controls behavior. The senses, motivations and feelings, sleep, learning and memory, language and consciousness, as well as their main disorders, will be analyzed in the conviction that knowing how they work is equivalent to knowing ourselves better and increasing our well-being and relationships with other people.

You can follow SUBJECT in Facebook, x and instagramor sign up here to receive our weekly newsletter.